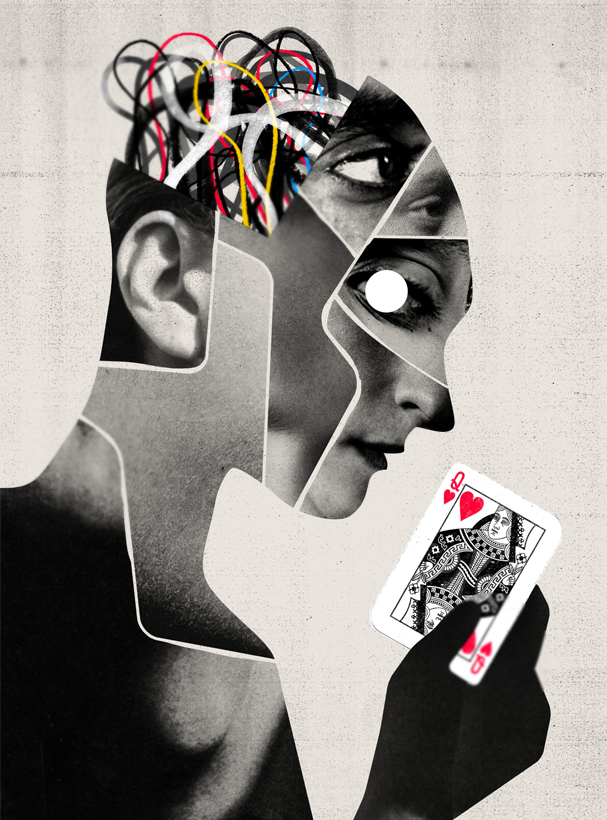

When an AI that monitors casino gambling in Reno taunts a magician by revealing all his tricks, the magician is determined to exact his revenge.

Best trick I ever saw? A lanky streak-of-piss Dutchman did it right in front of my eyes. A ring, a watch, a wallet. Some covering patter about a thief, but the effect is: He puts the ring, the watch, and the wallet in an envelope and seals it. Patter patter, he tears up the envelope and presto chango, it’s empty! The ring, the watch, and wallet are back on his finger, his wrist, in his inside pocket. Simple, quick, clean: done three feet in front of me and I have no idea how he did it.

Well, I do. Sleight of hand. Misdirection. That’s how they’re all done. But the trick of it —the guile: I have no idea.

I’m not a magician. I was the Silverado Resort’s valet parking service. Pernell Brolin.

I used to be a pit boss; eight pits, blackjack. I was hot death in a tux. I ran a tight pit. But, you know, age. You slow. You miss things. I still have a stripe down the side of my pants, but it’s gray, not black.

This is not a Las Vegas story. It’s a Reno story. And it doesn’t take place in the Luxor or the Bellagio, it takes place in the Silverado Resort. Popular with spring breaks and bachelor/ette parties from San Francisco. And it wasn’t David Copperfield or Mat Franco or Penn and Teller. It was Maltese Jack Caruana.

Those guys, they make 737s disappear or levitate Charlize Theron or drive semis over each other’s heads. Big, clever illusions. Jack Caruana is up-close, under-the-skin, inside-your-head magic. The kind of man who would take your ring, watch, and wallet without you ever knowing, and work wonders with them.

There’s a new thing in magic, like there’s a new thing in jazz and, it seems, in coffee. This new thing is to show how the trick is done, and then do it anyway. The skill—the guile—is in how well you perform the sleight of hand. Some of the new names in the Las Vegas hotels and magic clubs work this way now.

They owe it all to Maltese Jack Caruana.

I had some of that new thing in coffee. A truck came in for a few days on the west side of Buena Vista. It was not what I call coffee at all. Sour. Coffee should not be sour. But it was the new thing, it seemed. The thing about this new thing, the guile, is that if you don’t like it, the problem is with you, not the coffee. With you, not the magician.

The coffee truck lasted two days. Not enough business in Buena Vista.

Now this you’d call the meet-cute. Movies have their tricks and guiles just like magic. I’d come off earlies, flat out by eight thirty, someplace beyond dreaming, when bam! A hundred watts of blue LED flashlight shone through my eyelids and I was awake like someone ran a live wire up my ass. The light swung around the inside of the trailer, then moved off. I saw a slit of blue shining under the door. I heard the latch, I heard rattling, I heard swearing, I heard every single key on a fob try the lock. Not cops, then.

Cops are always the first thought in Buena Vista.

I pulled on a robe and threw open the door. I almost knocked the short, sixty-something man back off the step.

“Who the fuck are you?” he said.

“Au contraire,” I said. “Who the fuck are you?”

Maltese Jack Caruana, of course. Magician. Ex the relaunched Alon, starting a new residency at the Silverado, two shows a night, matinee on Sundays. Mondays off. He’d been given a trailer in our little clutch. Misread the key fob; two for five.

“You’re a magician and you can’t get a door open?”

He was small like some kind of terrier, and he looked exactly as someone would who’d driven up from Vegas in one go. He smelled of car seats, taco sauce, and dust and sweat, but it was the M-word that got him in my door. Magician.

“So what kind of magician are you?” I asked. ‘Illusionist, escapologist?”

He looked at me like I was bird shit on his shoulder.

“You know magic?”

“I know it. Can’t do it.”

“I’m a micro-magician and mentalist,” Jack Caruana said, and that got the top off my quart plastic bottle of blended scotch and two glasses on the coffee table. Of all the schools of magic, I like the up-close, intimate magic best. There’s nowhere for the trick to hide. Illusion: a magic box or a glass tank or a big circular spangled curtain and you think, okay, the trick is in there somewhere. Escapology: -one big trick—get out of this– and that’s it. Mentalism: old stuff —reading minds, predicting the future, clairvoyance, hypnotism, moving things with your mind, feats of memory. Micro-magic: up-close, table-top magic; hands and cards and you know it’s in the hands somewhere, but you never see it. That’s proper magic.

“Did you ever meet Ed Lorenzo down in Vegas?” I asked. “I like that guy. Makes me laugh.”

“Taught him everything he knows.”

Right, Jack Caruana. Magic men who residency in Las Vegas, even at the Alon, don’t domicile in Buena Vista. I poured and slid a glass across the table to him.

“Did you teach him that walking chair effect? Loved that effect.”

“Good effect, that.”

We clinked. You see, real magicians don’t do tricks. Real magicians perform effects.

“Maria won’t have cleaned the trailer out and you don’t want to start this time of night,” I said. “I got a spare bed in back. Welcome to Buena Vista, magic-man.”

It started when Salazar lost his job to the robot.

I say that and you think Arnie walking out of the exploding gas tanker or a transformo-bot the size of a city block punching its fist down a monster’s throat. Or maybe one of those cute Japanese things that I always want to kick onto its back to watch it flap its arms. But modern robots of the twenty-first century—real robots—are invisible. Now you’ve got another image in your head you can’t get out. I’m playing a magician’s trick—telling you the truth but making you see something else. Invisible killer terminators. Software, my friend. Software robots.

The house wins in the end. That’s the iron rule. You can win big, that’s probability, but if you win consistently, you’re gaming the gamers. The house calculates its edge by statistics—standard deviations—and when the shape of the bell curve starts going out of whack, it’s time to take a closer look. There is knowing when to look, and knowing what to look for. Salazar was the eye of the Silverado.

When I started in the pits, they used to hide the surveillance cameras. By the time I went to the concierge desk, they were in plain sight. Guys like Salazar worked twelve monitors at a time. You had to have the eyes, but you needed the nose as well. Psychology, my friend. Every player has tells—having no tell is a tell—and it’s no different for cheats. People who fiddle at their clothing all the time at the table but never at the bar. Patterns of blinking. Salazar took all the tiny improbabilities of behavior and made them into something significant, because there is nothing random about humans. Twelve years watching the pits and he pulled every kind of rigger and card-counter and memory artist, and then the casino pitted him against an AI. Remi. We all thought it stood for something. Remote Evaluation and Monitoring Intelligence. No. Didn’t mean a thing, just a name. But in the first week alone, Remi’s catch was up twenty-seven percent over Salazar’s. Over a month it was thirty-seven percent higher.

The entire surveillance team was moved to other work, and that is how Salazar the Eye came to Buena Vista.

AIs don’t see the way humans do. AIs have no blind spots, no doubts, no biases or unconscious skews, and they never, ever blink. Humans notice, humans select, and humans un-notice. AIs see. Like God.

If Salazar losing his job to Remi was where it started, it began the night I was sitting up for Jack to come back after the eleven o’clock show in the Opal Miner bar. Starting and beginning, they’re two different things. We’d begun taking a sundowner together at the end of the shift before we headed off to our trailers. Just one, maybe two. Never three. The casino had implemented random drink and drugs tests. Not that Jack ever would—a drunk magician is no magician—but I’m in a car-facing job and I’ve been in twice already to blow into the white tube.

High pressure was sitting over Reno like an alien mother ship—four days now and the heat was at insane and climbing. We were sitting outside on camp chairs surrounded by freezer packs full of slowly melting ice we’d collected from the hotel ice machines. Didn’t make a damn bit of difference. Jack’s cell rang. He answered and I saw a weird look on his face, then he raised a finger—something strange here—and then touched it to his lips—whatever you say, say nothing—and put the phone on speaker.

“Sorry, I got distracted, who did you say you were?”

“Come, come, Mr. Caruana, you weren’t distracted at all. I saw you on the twelfth-floor street-view camera. You have Mr. Brolin with you, and from your behavior, I suspect you are relaying me on speakerphone.”

Remi? I mouthed.

“Yes, Mr. Brolin.”

Fuck, I mouthed.

Jack kept his cool. “Casino employees aren’t allowed to gamble,” he said.

“You know I would know that, Mr. Caruana, so I wonder if you are attempting some kind of double bluff? I was watching your evening show.”

“What did you think of it, Remi?”

“I think that I am at variance with the audience.”

“How so, Remi?”

“They applauded the degree to which they were deceived by you. I applauded the plausibility with which you sold obvious misdirection.”

“I don’t understand, Remi.”

“I think you are being disingenuous, Mr. Caruana. For example, your opening piece. You clearly direct a member of the audience to pick a card you have preselected. You do it by observing the card at the very start of the trick and then manipulating it into a position to be selected. The audience is amazed when you identify the card you have already selected.”

“That’s magic, Remi.”

“There is no magic, Mr. Caruana.”

“You saw me make the force.”

“Yes. You directed the audience to look elsewhere while you very quickly noted the bottom card of the deck and slipped it to where you had cut the deck in a concealed hold.”

“That force takes less than a tenth of a second, Remi.”

“Point zero eight of a second. But I don’t see the way humans see, Mr. Caruana. I see everything, all at once. I am incapable of being misdirected.”

“That’s a very basic effect, Remi. I use it as a warm-up, really. You can see how to do it on YouTube.”

“But I didn’t see it on YouTube, Mr. Caruana. I saw you do it in front of eighty people, out of a maximum capacity of two hundred, in the Opal Miner bar. I am intrigued. I shall be watching you in the future.”

Call over.

“Fucking artificial fucking intelligence…” Jack ranted. The cell rang again.

“As I understand, that is a disrespectful thing to say, Mr. Caruana.”

I jerked a thumb toward the hotel, turned my back to the camera, and said, “It can lip-read.”

Every show that week, Remi watched, two shows a night and the matinee on Sunday. Every night, as we slumped off the shuttle bus and into our chairs under the heat that showed no sign of breaking, it would call and tell Jack exactly how an effect was worked. It started on the easy, sleight-of-hand tricks. By Wednesday it was dismantling the showstoppers.

“It must be researching,” I said. “Everything on YouTube, all the Magic Castle videos, every magic show ever done. It wouldn’t take it that long.”

“It doesn’t need to,” Jack said. “It does exactly what it says. It sees in a way we don’t. I can’t misdirect it. Watch this.”

He stood up, pulled a deck of cards out of a pants pocket. Shuffle, cut. “Pick a card.” I picked the Queen of Hearts. Jack shuffled the card back in, squared the deck, put it back in his pocket. “I’m going to read your mind, then I’m going to use my mind to steer your mind to pick exactly that card in the shuffled deck.”

He pulled out the deck, fanned through it.

“Any time you want.”

“Stop.” He turned up the card. Queen of Hearts, of course.

“Simplest trick in the world.” He let the cards fall. They were all Queens of Hearts. “It’s a force and deck-swap. I put the first deck in my right pocket, but the marked deck, I take that out of my left pocket. And no one ever notices. Remi would see through that in a second. I wouldn’t insult it, or myself, with that effect. You know some magic. You know every effect is made up of key parts…”

“I saw that movie,” I said. “The pledge, something in the middle I can’t remember, and the prestige.”

“That’s structure. How magic works, that’s different. In my theory…”

“Everyone’s got a theory,” I said. I passed the big plastic jug of whiskey. Down to the last two fingers. Three days to payday. I should stretch it, but I love magic talk.

“In my theory,” Jack said without losing a beat—he knows how to work an audience—“every effect has two elements, the guile and the panache. The panache is all the showmanship, the patter, the props, the dressing. The panache is how you sell the effect. But the trick, the magic: That’s the guile. The panache is there to hide the guile. People see the panache and miss the guile. Remi doesn’t see the panache and nails the guile. Every time. I do the purest magic there is, and he sees the guile. Every time. He’s probably lip-reading this right now. Read this, then, Remi. There has to be an effect, somewhere, that an artificial intelligence can’t see.”

Inés rolled in off the shuttle bus. She used to deal pai gow poker but as she got older and stiffer she got moved down the tables, pai gow poker to baccarat, baccarat to blackjack, blackjack to the slots. Now she bossed a pit of twenty-five machines.

That was her road to Buena Vista.

You see me in the gray frock coat and the pants with the stripe down the side and the shoes so shiny its like they’re signaling to the moon. I say, Welcome to the Silverado ma’am, and I take your car and off I glide, and when you want it, back I glide. The panache. You don’t see the big concrete underground garage. That’s the machinery. And you don’t see me at the end of shift taking the staff shuttle bus out the back way, along the boulevard through the gate in the screen of trees. Behind those trees is Buena Vista Trailer Park. Right in the middle of Reno’s premier resort hotels, the trailer park no one sees.

No one except Remi, it seems.

Inés banged down beside us on a camp chair.

“Air-con still dead?”

“Can’t have this heat, Pernell.”

Inés’s air-con was perfectly serviceable. She hadn’t been able to pay her power meter the past month. She’d been eating on the staff discount and lighting the trailer with candle stubs stolen from the banqueting suites.

“I hear that computer’s upstaging your show, magic-man.”

Jack scowled. I offered her scotch.

“If it were me, I’d show that uppity machine what for.”

And then it came to me, oh Lord it came to me, in a kind of sparkling flash and everything was still and silent in all the world. I jumped right up out of my seat. Pretty spry for my joints.

“I’ve got it!” I yelled.

Scotch flew everywhere.

“It’s obvious! Gandalf versus Thulsa Doom!”

My pa, he had a trick. Everyone’s pa had this trick. He put a little piece of paper on each finger and went, Two little birds sitting on a wall; one called Peter, one called Paul. Well you know how it’s done, but at age eight I watched and I watched until everyone was pissing with laughter because I couldn’t see he was making them fly away and come back. Same as Jack’s Queen of Hearts; you’re so busy watching you don’t see.

The idea that magic was as simple as swapping forefingers with index fingers made me a lifelong fan of tricks and scams, fakes and fly moves. I begged and begged to get a magic kit of my own for my twelfth birthday, but I learned pretty soon that I didn’t have the motor skills—or the dedication—to work a palm or a drop. There is no performance art rehearsed like magic. Thousands—tens of thousands—of repetitions: Magicians practice a move until it’s automatic, perfect, instant and unseen.

I couldn’t learn the guile.

In community college I always sat in the same chair. One day I got moved to a different one. Someone had carved into the folding table: Gandalf v Thulsa Doom. Deep and smooth at the edges, filled with black gunk like it had been done back in the sixties. Even when I moved back to my usual seat, it bothered me. Gandalf I’d heard of, but who was this Thulsa Doom? The undead sorcerer in Conan the Barbarian, that’s who. James Earl Jones, that’s who. James Freakin’ Earl Jones.

And it all came back. I’d never seen a black wizard before. I don’t mean dark arts, evil magic. I mean: black. Wizards were old white guys with beards and staffs. No disrespect, Mr. McKellen, but this was a black guy who looked as mean as fuck and could turn into a giant death snake. James Earl Jones as Thulsa Doom: That’s a wizard I could get behind.

I hadn’t thought about those old words gouged into the community college desk for years. But it lay there, unseen but not forgotten, until one hot, high-pressure night in Reno, it came bubbling up.

“A challenge.”

I knew Jack wasn’t getting it with the same white, Saint Paul–blinding light in which I saw it. This would be a sell.

“The challenge, my friend. You, Maltese Jack Caruana, international man of mystery, magic, and mentalism, challenge the great Remi, all-seeing wizard of the Silverado, that you will perform a trick, before a live audience, that it cannot explain. Marketing, my friend. Is. Everything.” The plan was clear and entire before me. I had a vision. “Battle of the wizards. Gandalf versus Thulsa Doom.”

“I could be wrong here…” Salazar was a less frequent visitor to the evening sessions than Inés, but he did chip in for the scotch. We were a small, tight community; four trailers drawn in around an open yard in a quiet corner of Buena Vista. We all chipped in what we could, when we could. “But that’s more Gandalf versus the all-seeing eye of Sauron.”

“The point,” I said, “the actual point is: You market it, you make it the biggest magic show in Reno—bigger even than anything in Las Vegas. The biggest show in the world. I tell you, you’ll get every magician and table-worker and illusionist and mentalist on five continents turning up to see this. It’s the classic battle—man versus machine. Like that chess master taking on Big Blue, or whatever.”

“Deep Blue,” Salazar said. Know your enemy.

“That chess master lost,” Jack said.

“Your career’s finished anyway,” Salazar said. “Like mine. Another robot kill. If you stop talking to Remi on the phone, it’ll break in on the sound system. If you shut down the sound system, it’ll just post the camera feed on YouTube. This way, you keep a percentage of the house and the licensing deal and a story for the after-dinner and convention circuit.”

“You’ve got this all thought out,” Jack said, and I knew I had him.

“Looking at ways to game the system is my job,” Salazar said. “Was.”

“Wizard Wars!” I said. “Or Wizard versus Wizard. Which sounds better?”

Then came a cry from Inés’s trailer and a sudden, flickering light. She had knocked over one of her candle stubs. Her curtains were on fire. Salazar pulled open the door, I went through like a linebacker and hauled Inés out. Her hair was singed, her hands scorched. Her sofa was ablaze. Black smoke boiled up from the burning upholstery foam. Then Maltese Jack was in with the fire extinguisher, sending tornadoes of powder to every corner of the trailer. The fire was out in moments. Powder covered every surface. The trailer leaked smoke from door, windows, every vent. It would be weeks before Inés could live there again, if ever.

“You stay with me tonight,” I said. Pernell Brolin, refuge to the lost.

We knew then we had to get out of Buena Vista.

The management didn’t go for either Wizard Wars or Wizard vs Wizard. They had their marketing department take a look at our proposal and decided to call it Magic or Machine? Like a Discovery Channel show.

Which is to say, they bought into it two hundred percent. A thousand percent. They bought it. The dudes who developed the software bought it. The papers, the syndication shows, the networks, and the digital channels: They bought it. The other casinos in Reno bought it: They wanted to see if Remi was as good as the Silverado said it was. And the public bought it.

Maltese Jack’s agent negotiated him a percentage of house and rights. It was a sweet deal. The Silverado added a rider; every trick that Remi guessed, Jack would never perform again. We both read the score: a Las Vegas magician on the glide-path of his career, who couldn’t even fill the smallest bar in the resort. It was the mother of all resignation letters.

So, you’ve had the meet-cute. Now the montage.

We had a date: Halloween. Of course. We had a venue, the Gold Room: the Silverado’s four-thousand-seater prime ballroom. Full light, sound, and projection. Willie Nelson filled it ten years back, ten nights in a row. Jack Caruana had one night, and he could have filled it ten times over.

Maltese Jack’s problem: There are only ten magic effects. Vanish, produce, transform, restore. Transpose, transport, escape. Levitation, penetration, prediction. Everything else is panache. Remi knew all ten.

Maltese Jack’s problem: part two. The kind of magic he performed was small scale, close up, unshowy. Making it fill the Gold Room was an issue. Big flashy displays, glam assistants in fishnets and smiles, would make the audience suspicious and kill it dead. Possible solution…

Add celebrities. The guest list for the golden circle was so full the Silverado had to start star-rating the celebs. Fellow magicians—only if they’d had a network series, a residency of more than six months, or seven million YouTube hits. Movie stars—only if promoting something that would be premiering at the time of the show. Sports stars. Supermodels. Millionaires, no chance, billionaires: step right up. Bloggers, vloggers. Influencers. Musicians? We could have filled the Gold Room with needy pop stars and had them spilling onto the gaming floor. Celebrities had the panache. Pick a star, pull them up onstage, and stick a camera in the face to see the OMG! expression all over the screens. Who needed flash and fishnets?

The publicity grind. The media training, the interviews, the photo shoots and profiles. The Silverado moved Jack out of Buena Vista to a penthouse suite. Inés took over his trailer. Management still hadn’t gotten round to fixing the fire damage. When our shifts allowed, Jack invited us up to abuse the bar.

“Look at the size of the bathroom,” Salazar said. “You could fight a war in here.”

“Egyptian cotton,” Inés said, stroking the sheets. Her hands had healed after the fire but the pain had set into the nerves and would likely never leave again. “What’s the thread count?”

“You can see all the mountains,” I said. I was out on the balcony. Cooler now, a different season.

“Planes coming in,” Salazar said, joining me.

“Where are our trailers?” Inés asked. From the penthouse level we could see Buena Vista at the center of a ring of casinos.

“It’s like a walled garden,” Salazar said.

“Some fuckin’ garden,” I said.

“Way to the right,” Jack said. “You can’t see them. The trees get in the way.”

It was pleasant on the penthouse balcony, with hundred-dollar bourbon and a cooling breeze from Tahoe, and it all said, Halloween is coming, and Maltese Jack Caruana: Are you ready? Do you have the effect that will fool an artificial intelligence that knows every trick and cheat and slick move a human can pull? Because if he did, he sure wasn’t telling me.

On the night, he called it right. The Silverado wanted tux minimum; silver lamé preferred. Maltese Jack walked on in the same slightly tight, cheap gray suit he wore for all his shows. At least a hat, the dresser said.

“Hats are for Sinatra,” Jack said.

So on he came, a small man in his early sixties in a bad suit. Onto the biggest stage of his life. He was on his mark before the follow-spot found him; it was another twenty seconds before the audience realized who he was. We started the applause. He had reserved us a table. Not the best, not in the golden circle, too close to the bar and we had to share it with a team from Boing Boing. He waited for the applause to die down.

“Good evening. I’m Jack Caruana. And I’d now like to introduce my partner and worst enemy, the machine that will decide in front of this specially invited audience and all these cameras if there really is such a thing as magic. Remi, the house AI.”

Remi’s voice boomed from the sound system. “Good evening, Jack. Good evening, guests and everyone watching on television,” and oh my days, the Gold Room went apeshit. Jack went down to a table in the golden circle and an actress I kind of recognized from those car-stunt movies gave him a big black book.

“My book of tricks,” Jack said. He put it on an honest-to-God church lectern. “My grimoire.”

Grimoire: that’s a good, mouth-filling word. Thulsa Doom would sure as shit have a grimoire.

He led with an old one, an easy one; a gussied-up variation on that same force that Remi had spotted and called us on Jack’s cell to discuss. Even I could see how it was done. Brian Hoyer from the Patriots, who’d come up waving and smiling to pick the card, was stunned. The room went silent as a morgue, waiting to see what Remi made of it.

“I am disappointed, Jack,” Remi said. “Very disappointed. Really, the bottom card force? That was the very first trick I learned.” Whoever was on the sound desk managed to make him sound even more irritating and petulant than he was on the phone. Remi spent five minutes taking Jack’s effect apart to the last finger-flick and thumb-hold. The entire Gold Room was spellbound. Jack Caruana stood smiling.

“That your last word Remi?”

“It is, Jack.”

“Well, Remi, our deal is, if you can see how the trick is done, the trick is gone. You saw it. That trick is gone. Dead. Buried.” And Jack strode over to the grimoire, tore out a page, and held it up for all to see. A flick of the fingers, a flash of blue fire, and the page was floating ash. Oohs. Flash-paper; always a nice piece of theater.

Next Jack brought one of those new country and western singers onstage. A decent prediction effect, a bit of number magic. Applause. Camera close-ups of amazed faces at the celeb tables. The pause—the AI equivalent of clearing your throat. Then Remi explained how he had done it in such detail, the whole Gold Room could have gone home and performed it.

Jack went to the grimoire; another spell from his book of tricks went up in a blue flash.

The French Drop. The Blackstone Cardless Card Trick. The Talkative Clipboard. Twisting the Aces. Classic effects, all of them. And Remi destroyed all of them in that patient, geeky, reasonable voice. Each dead trick, a page went up in blue fire from the book of magic. At first the audience had laughed and applauded when Remi told them how the effect was done. Then I noticed them sit back and sigh and murmur, and those murmurs become rumbles of displeasure. Because Jack was losing to Remi, but Remi was losing the audience. Remi didn’t know, didn’t care. Remi didn’t see the panache. Remi only saw the guile. And that was its mistake.

Hummer Card, Mexican Turnover, Scotch and Soda, the Reluctant Telepath. Dead, dead, dead. Dead. I felt the Gold Room turn, I felt the anger and silent resentment, from every pit-watcher who lost his job to an AI to the singer who’d been auto-tuned until every atom of individuality had been polished out of her voice, every musician who’d had an AI take her song, drop it around beats and boops and turn it into some shiny, soulless global megahit. Every ball-player and tennis star and golfer who’d had their game taken apart and analyzed and drilled by a machine coach again and again and again to do it right do it right do it right. And I saw that the real loser was Remi.

Jack went to the grimoire, opened it to let the final page hang down.

“All gone,” he said. “Every trick in the book. Except one.”

Every magician keeps the big effect for the finale. Leave them astounded. The Gold Room went quiet. Even the bar fell silent. Not a camera-whir, not a notification alert. Jack went down into the golden circle and led Taylor Swift up onto the stage.

Everyone in the Gold Room was on the edge of their seat.

Jack delivered some quick-fire patter, let Taylor promote the new album, then said, “I’m going to show you a deck of cards.” He took a deck out of his right pocket.

I whispered, No, Jack, don’t do that. You can’t do that. Not for the last effect.

He did the force and the switch, right pocket–left pocket. The worst, the best, the most bare-faced trick in the world. Queen of Hearts. They’re all Queens of Hearts. A silence in the Gold Room. Was that it? Was that the trick that Remi couldn’t solve? Applause started—not by me—broke into a ripple, into a cautious wave. Obviously something very, very clever had happened here. Something Muggles couldn’t see, something not even Remi could see.

“Jack.” The Gold Room held its collective breath. Cameras went in close on Jack Caruana’s face. “Jack. You took the first deck from your right pocket. You took the second from your left pocket.”

The Gold Room exhaled. They hadn’t seen it. They truly had not seen it, the most blatant, most stupid, most obvious trick in the grimoire. In that instant, they hated Remi. He had shown them something obvious, right in front of their eyes, that they hadn’t noticed. Any kid could do that trick. It had fooled four thousand people, live in front of cameras. Remi had just told every celeb and sports star and the guys from Boing Boing that they were blind and stupid.

Jack ripped the final page from the grimoire and held it up. A click of the fingers and it was consumed in blue fire.

“Ladies and gentleman, the machine has won. It was a privilege to perform for you the night the magic died.”

Then he walked down from the stage and up between the tables toward the ballroom’s main doors. The Gold Room rose around him. Roaring, cheering. Whistling and yelling and whooping. Because no one wants the magic to die. No one wants to know how the trick is done. We want wonder in the world, things we can’t explain. We want to be fooled, even though we know there is no such thing as magic. It’s always a trick. It’s the quality of the trick—the guile— that matters.

Jack Caruana walked through those tables and out the double golden doors, clean out of the Silverado, and never once looked back. A beaten man, triumphant.

And that’s the panache.

We waited until the celebs and the movie stars and vloggers had all gone, until the TV crews were coiling their cables and de-rigging their microphones. Salazar and Inés and me, we went to the elite pickup zone and waited on the red carpet between the golden ropes. Perfectly on cue, the executive van with the blacked-out windows pulled in.

Jack already had the champagne open.

“Airport, sir?” the driver said. Adnan had booked the executive van two months before.

“How much time have we got?” Jack asked.

“Time for whatever you want,” Adnan said.

“Take us the tourist route,” Jack said. We went round Buena Vista, all the way, three times, drinking the champagne as we wove between the shuttle buses. Then Adnan drove us downtown through the neon and we drank the second bottle of champagne in the blue-green flickering light.

“I thought I was going to shit myself when you did that dumb-ass two-pocket force,” I said.

“Run the risk of a new trick that just might work?” Jack said. “The pocket switch was a sure bet.”

There is a proverb in magic: Make the audience walk as far as possible from the trick to the effect. In the best effects, the guile happens even before the magician has told you what the trick is about. If the vigorish gets you in the end, the wise bet is on the house. We played Remi to lose. If Jack had beaten the AI he would have been locked up in the Silverado forever, performing that one trick again and again and again. Hey! Give us the trick that beat the computer! Again and again and again. With every eye in the Gold Room watching his every flick of a finger to spot the guile that the computer missed.

We made it out clean and there was a plane on approach high over the desert, coming to take us down to Florida.

Fly away Peter, fly away Paul. Fly away Inés and Salazar and Pernell and Jack.

But the best tricks—the very best tricks—have the twist in the end. The kind of trick where you borrow someone’s tie and cut it into pieces, then forget about while you do the real trick and then at the very end, when tie-guy is the only one remembers what you did, you bring it back whole again.

“How much did you take them for?” Jack asked as Adnan brought bags round to the curb.

“About a grand,” Adnan said.

Remi boasted that it did not see as humans saw, that it could not be misdirected. But a magician will tell you: They don’t deal in misdirection. They deal in direction.

Staff can’t gamble at their own casino. But their friends, relatives, workmates at other place of employment: They can. Remi studied us, but it never occurred to it that we might study it. Learn its tricks and guiles. While Remi was watching Maltese Jack Caruana up there in the spotlight, a hundred gamblers hit the Silverado’s two floors. The casino was packed that night, players watching the Wizard Wars as they fed the machines. Our foot soldiers worked the tables, made money, moved on. Made money, moved on. Made money, cashed up, and rolled on out. The bank of Buena Vista. Remi never saw, because Remi was watching Jack.

And that’s the guile.

And that’s the story of how Maltese Jack Caruana beat the machine.

What ya mean, you didn’t see it? Where were you? Mongolia? Jail? It was all over the networks. It’s up on YouTube. Just Google it. Wizard Wars, Wizard versus Wizard. Even Magic or Machine, God help us. Any of those will get you there.

Anyway, thanks for the drink. Should be heading back. I’ll call an Uber, thanks. It’s pretty close. Yeah, we all have apartments in a gated community. No it’s not fuckin’ Cocoon. I don’t need to be mentalist to know you were going to say that. You all do. It’s nice, a pool, tropical planting. Wi-Fi, gym, store. Golf buggies to get around when we want to visit. No, not a beachfront location; who can afford that? But you can smell the ocean in the morning, and on a quiet night, you can sometimes hear the waves.

You see, it’s the things you notice and the things you miss. Did you notice that I never explain why Jack was called Maltese Jack? Nor will I. Just recall what I said about the best tricks having a turn at the end. You see, I called this story “The Guile,” not “The Panache.” And I also said that the smart wizard makes it a long walk from the guile to the panache. The effect. The magic.

You see, Thulsa Doom may be the first black wizard, but he isn’t the only one.

Maybe check your watch, your ring, and your wallet, my friend.

The author would like to thank Alan Kennedy for his (guile-less) help with matters magical.

Text copyright © 2018 by Ian McDonald

Art copyright © 2018 by Keith Negley

Ian McDonald’s novella Time Was is now available from Tor.com Publishing.

Buy the Book

The Guile